The new CPU partner In a turn of events, IBM agreed to share its IP and to design a new multi-core processor, and so the Xbox 360’s CPU supplier became IBM. Although, you may remember this was the same IBM that already signed an agreement with Sony and Toshiba to produce the Playstation’s 3 CPU (‘Cell’). Apparently, IBM assumed Microsoft was not aware of the Cell project [3] and their current contract with Sony didn’t forbid them to sell to third parties.

All three companies [IBM, Toshiba and Sony]… legally all had rights to go and put any of that technology, any of those processor cores into other spaces. (…) It is very common to develop an interesting, leading-edge new technology and then utilize that technology across multiple platforms. (…) I guess what everyone didn’t anticipate was – before we even got done with the Cell chip and PS3 product – that we’d be showing this off specifically to a competitor. [4]

– David Shippy, chief architect of the Power Processing Unit (PPU)

Ironically, as of 2022, IBM’s PowerPC chips have vanished from both desktop computers and video consoles, maybe this set a bad precedent and greatly affected IBM’s trust in future businesses? I’m afraid I don’t know the answer to that.

To sum it up, IBM signed an agreement with Sony and Toshiba to develop Cell in 2001. Two years later, in 2003, IBM agreed to supply Microsoft with a new low-powered multi-core CPU. Microsoft’s CPU will be called Xenon and will inherit part of Cell’s technology, with extra input from Microsoft (focusing on multi-core homogenous computing and bespoke security). Also, while IBM would brand Cell with its ‘BladeCenter’ line of servers, Xenon could only be fitted on an Xbox 360 motherboard.

Cell’s half-sibling

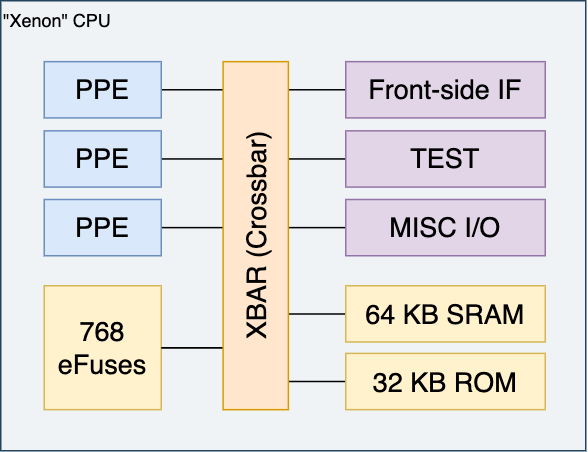

Now that we positioned Microsoft and IBM in the map, let’s talk about the new CPU. This is how Xenon materialised at the end of the Xbox 360 project:

The Cell project, with its obsession with vectorised computations, introduced very interesting proposals to radically tackle the ongoing constraints that hindered technological progress. These constraints, however, are very complex. So it wouldn’t be fair to say that Cell’s methods were the only -or even best- solution. In other words, by studying Xenon’s architecture (which competed side-by-side with Cell’s) we can gain a different perspective on how CPU architecture evolved throughout that era (the early 00s) and subsequently influenced the next decade of CPUs.

Xenon chip, surrounded by an army of decoupling capacitors. In doing so, you’ll perceive that Xenon takes a more conservative approach than Cell. If we take another look at the previous diagram of Xenon, you can notice that the latter is equipped with the famous PowerPC Processing Elements (PPEs), which is also the most important piece of Cell. However, Xenon’s is now equipped with three of them. Additionally, the Synergic Processors Units (SPUs) are no more.

After all, Microsoft didn’t want processors of very different natures squashed in their CPU. They instructed IBM to compose three powerful cores and enhance them with the ingredients game developers would expect to find. With this approach, IBM and Microsoft were also able to add non-standard features without disrupting the traditional modus operandi of developers.

Truth to be told, this also resulted in aggressive budget cuts to keep this design (and the rest of the system) at a competitive price range. To put it in context, multi-core CPUs for PCs weren’t on the store shelves while IBM was building Xenon, and when they debuted in 2005 (coincidentally, the same year the Xbox 360 reached the stores), AMD priced their cheapest Athlon X2 at $537 (equivalent to ~£452 in 2021 money) and Intel charged $241 (equivalent to ~£203 in 2021 money) for their low-end Pentium D [5] - and let’s not forget the box only included the CPU. How this study is organised We’ll now take a look main components that comprise Sony’s counterpart. To avoid repeating existing information, I’ll focus on the novelties of Xenon.

Having said that, the new CPU runs at 3.2 GHz and it includes so much circuitry that, for this study, we have to split it into different groups:

The three leaders that execute the program’s instructions. At first, each resembles Cell’s PowerPC Processing Element (PPE), but you’ll soon see that they are actually a superset of it. Additionally, since we’ve got three of them now, it may seem as if the whole chip behaves like a Ceberus monster, where each core may claim control of the whole system. Alas, that’s not feasible in a computer, so the first core is the designated master core while the others will be taking assistant roles. A single interface that interconnects the cores with the rest of the system. This bus is called XBAR (pronounced ‘Crossbar’). Like in Cell, there are other proprietary interfaces used for debugging or maintenance (i.e. temperature) but these will not be mentioned until we reach the ‘Anti-piracy’ section. The security block which Microsoft oversaw to implement the anti-piracy system. It’s a very complex section, so to avoid overwhelming you with information, I’ll explain it in the ‘Anti-piracy’ section as well. The different approach for Xenon To explain the aforementioned groups, I’ve organised the study of Xenon into these areas, in that order:

The bus connecting all the cores, the XBAR and its special L2 cache block. The new refinements of the PowerPC Processing Element (PPE). The unusual abundance of general-purpose memory. The new programming model suggested (and, in some ways, enforced) by Microsoft. Inside Xenon: The messenger The original chip (Cell) was required to house twelve independent nodes actively moving data around, this forced IBM engineers to devise a complicated system that could tackle emerging bottlenecks, which materialised in the form of the Element Interconnect Bus (EIB). With the Xbox 360, Xenon only accommodates three units (the three PPEs), so the EIB has no purpose here. Thus, a simpler solution called XBAR was produced to solely focus on the three PPEs, with space for extra functionality.

XBAR relies on a mesh topology that doesn’t direct traffic in a token-style manner. Instead, each node is provided with a dedicated lane to move its data through [6]. This may appear more optimal than the token topology of the EIB, but that’s because the XBAR only needs to serve a small number of nodes. Furthermore, the XBAR operates at full speed (3.2 GHz).