One idea is that 24! ≈ 1024 and 25! ≈ 1025.

For every n, there is some base b such that n! = bn. For example, 30! ≈ 1230.

It’s easy to find b [1]:

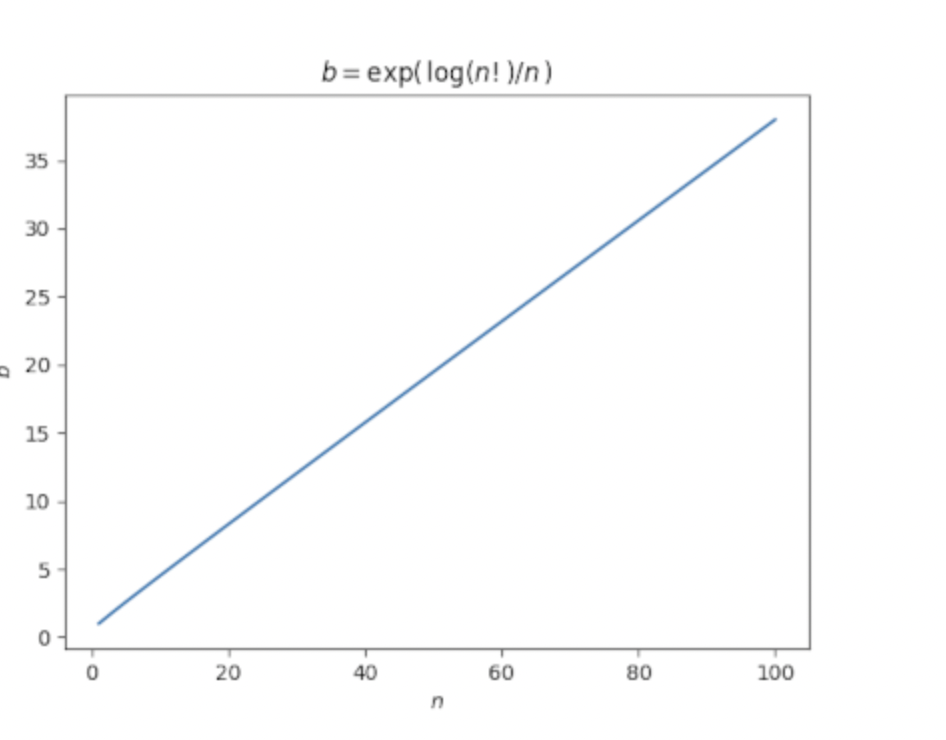

b = \exp\left( \frac{\log n!}{n} \right)

What’s interesting is that b is very nearly a linear function of n.

In hindsight it’s clear that this should be the case—it follows easily from Stirling’s approximation—but I didn’t anticipate this before I plotted it.

Now fix n and find b such that n! = bn. Since the relationship between n and b(n) is nearly linear, this suggests

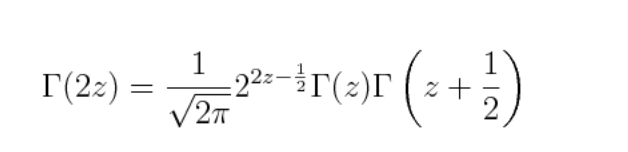

which is true. It follows from the multiplication identity for the gamma function:

Let z = n + 1/2 so that the left side is (2n)!. On the right side, Γ(z + 1/2) = n! and Γ(z) is not too different from n!. The rest of the right side is 22n/√π.

So our observation that b(n) is nearly linear gave us a hint of Gauss’s multiplication formula.

[1] Numerically you would probably evaluate this function by calling a routine that computes log Γ(n + 1) directly without computing Γ(n + 1) first. This avoids overflow for large n.

This is why mathematical libraries will have not only gamma functions but also loggamma functions. The latter seems redundant, but it’s not (math library functions are rarely redunant).