Deriving the properties of chemicals from their molecular structure is one of the central goals of chemistry. In principle, all properties of a molecule can be determined by their structure. Unfortunately, molecules are quite complicated to say the least – especially when they interact with other molecules. Hence, using machine learning has become instrumental for molecular property prediction. Molecular machine learning holds a lot of potential to speed up drug discovery and will help us answer fundamental questions about the behaviour of molecules. However, before we get there, we still have much to learn about how to build good models.

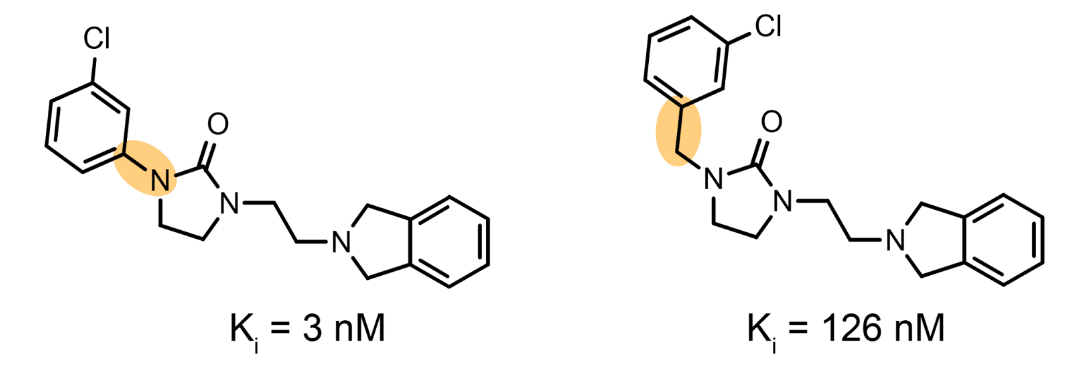

One important topic left relatively unexplored is how machine learning models behave in the presence of Activity cliffs. An activity cliff appears when a small change in molecular structure results in a drastic change in its bioactivity (or other molecular property, see Fig. 1)

. This term was coined by Gerald Maggiora [1] and is a reference to sudden changes or ‘cliffs’ in the structure-activity landscape.

Figure 1. An example of an activity cliff. Two molecules differ only slightly, but exhibit vastly different bioactivities. Bioactivity is experimentally measured in Ki or EC50. Here a lower number means that you need less molecules to achieve a certain biological response, i.e., the molecule is more potent.

We know that for many drugs, a tiny change in a molecular structure can sometimes make a huge impact. Knowing which structural changes strongly affect bioactivity can tell you a lot about how a molecule interacts with its designated target (e.g., a specific protein involved in a disease). At the same time, it is well-known that activity cliffs can be troublesome for machine learning models to predict. For this reason, one could see these extreme scenarios as good test cases for molecular property prediction models. Besides, the presence of highly similar molecules is very common in commercial libraries that are used for prospective applications like drug screening. Therefore, models that are not able to distinguish the effects of small molecular changes are probably not your best option in prospective settings. Still, even though activity cliffs are important in molecular data, we don’t know when, why, and how machine learning models tend to fail in their presence. Therefore, we set out to illuminate the failure modes of common ‘out-of-the-box’ methods for bioactivity predictions in the presence of activity cliffs.

One of the first difficulties of quantifying the effects of activity cliffs is the definition of activity cliffs themselves. Because we wanted to sketch a general picture that applies across the board, we tried to combine three types of molecular similarity (substructure-, scaffold-, and SMILES similarity) into a well-rounded definition of activity cliffs. Details can be found in our paper [2].

The data

Because we want to measure the general effects of the presence of activity cliffs on model performance, we composed 30 different datasets from ChEMBL [3], covering a wide range of training scenarios and target proteins. We thoroughly cleaned and curated this data to minimize noise and ‘fake’ activity cliffs. To maintain a similar distribution between molecules in the train and test data, we clustered molecules by their structure and used random stratified splitting by their activity cliff status into train (80%) and test (20%). In other words, we enforced similar proportions of activity cliff compounds in the train and test set.

[1] Maggiora, G. M. On outliers and activity cliffs–why QSAR often disappoints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 46, 1535 (2006).